Word has it that the folks who fish the waters off Puerto Ángel really know how to find fish—tuna, red snapper, bonito, saltfish, and shark, along with lobsters, octopus, and conch. The fishermen go offshore, out to open ocean, over a shallow area with a well developed, multi-layered coral reef. Hmm. How did a reef get out there?

Well, first came an undersea volcano. This particular one—among hundreds if not thousands that form at the edges of tectonic plates as they struggle for position along the Pacific Coast—blew its top in 1803 and again in 1875. The records don’t say much else. Given that volcanology was pretty much basic observation at the time, the volcano must have breached the ocean surface.

Remember Your Fourth-Grade Geography? Plates and Quakes?

If you spend a lot of time on the Oaxacan coast, you know it’s one of the most earthquake-prone areas in the world. The prime mover in shaking the earth is those tectonic plates. Right off Puerto Ángel, the relatively small Cocos Plate has been trying to sneak under the North American Plate since time immemorial, probably 20 million years ago in the early Miocene Epoch. This “subduction” caused an unusual upheaval running crosswise under the major mountain ranges of Mexico, from Jalisco in the west to Veracruz in the east (most volcanic belts run within or parallel to mountain ranges).

The upheaval pushed up volcanoes as it went, of which at least two are still active—Nevado de Colima (Jalisco) is just quieting down after three years of belching lava, ash, and smoke, while Popocatépetl in Puebla has been erupting since 2004. (Movement of the Cocos Plate caused the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, which killed over 5,000 people.)

The submarine volcanoes are created as molten rock (magma) escapes along fissures in the ocean floor. The great majority of fissures are located at the edges of plates jockeying for position—the plates are floating on the mantle of magma around the earth’s core and when they meet up, it’s not cute. One slips under the other or they slip against each other, pieces break off; hence, earthquakes (terremotos), seaquakes (maremotos), the occasional tsunami, and . . . volcanoes!

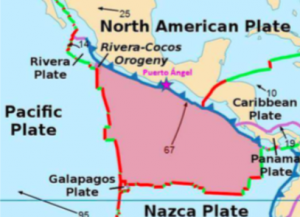

At this point, the Cocos Plate is hemmed in by other plates, with the very large North American Plate to the northeast and the very large Pacific Plate to the west. The smaller Rivera Plate is on the northwest, and the mid-size Caribbean and Nazca Plates are to the east and the south, respectively. On the map below, the arrows indicate the direction of plate movement, and how many millimeters per year the plate is moving. Cocos is moving northeast, under the North American and Caribbean Plates, at 67 mm., or just over 2.6 inches, per year.

The movement causes minor, imperceptible quakes along the Oaxacan coast practically every day. Maybe every 8 to 10 years, there’s a magnitude 5-6 earthquake like the one on April 10, with its aftershock on April 11. Magnitude 7-8 quakes happen every 70-100 years; a quake that size can generate a small tsunami. At 11:30 on May 11, 1870, five years before the submarine volcano erupted, there was a magnitude 7.9 earthquake with an epicenter in Pochutla.

The quake was accompanied by a loud subterranean noise that made “the stones leap from the earth,” Miahuatlán and Pochutla fell into ruin, there were great cracks in the fields and rockslides in the mountains. The earth was so hot you couldn’t walk barefoot, and at the shore in Puerto Ángel, “the sand and the sea bubbled and boiled.” In Santa María Tonameca, west of Pochutla, most buildings were lost as well, but from beneath the ruins of the Catholic church, Tonamecans rescued a carved cedar statue of the Virgin of the Assumption, the town’s patron saint. This was greeted as a miracle, and Tonameca hosts the largest festival in the area on May 11 to celebrate the Virgin’s survival. Events last eight days, and represent a fascinating mix of pre-Hispanic and Catholic elements. There is a grand parade and a guelaguetza (dance festival with dances from the seven regions of Oaxaca), not to mention a rodeo, cockfights, lots of drinking (“ritual intoxication”) and fireworks.

The Making of a Submarine Volcano

It’s not surprising that we don’t have much information on the Puerto Ángel submarine volcano (technically, it’s called the Submarine Volcano of Pochutla) and its reef, because it’s hard to catch submarine volcanoes in the act (less than 4% of recorded volcanic eruptions have been from submarine volcanoes). And by worldwide standards the Puerto Ángel volcano would have been fairly small. However, several submarine volcanoes have been “born” in the 20th – 21st century, so the process has been well observed.

On November 14, 1963, a volcano breached the surface of the Atlantic just south of Iceland. And when it breached the surface, it was a sight to behold. It started more than 400 feet below the ocean surface, and the eruption was characterized by giant clouds of smoke and steam, extensive volcanic lightning, and fiery flows of lava.

Named Surtsey, after Surtr, a mythic Norse “fire giant,” it sits on a fissure in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (the boundary of the North American and Eurasian Plates). Surtsey continued to erupt for four years, pouring a lava “cap” over the surface of volcanic ash. Although the sea has reduced the island to about three-quarters of its original size, Surtsey’s lava cap has protected it from being completely eroded, and it has developed plant and animal life.

Most submarine volcanoes never get that far, collapsing or being worn down into “seamounts.” These have traditionally been mapped with bathymetry, profiling the ocean depths with ship-based sonar. A new effort using satellite technology to map the sea floor gives an even better idea of what the Puerto Ángel seamount looked like before the reef started to grow.

Researchers at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography at the University of California at San Diego have combined two types of satellite data that map “gravity fields.” Combining the satellite data with other ocean sensing data, the researchers can identify thousands more undersea basins, mountains, and the ridges where plates meet and earthquakes occur (the edge of the Cocos plate along the Oaxacan coast has an “aura” of earthquake dots).

It works because satellite altimetry can produce precise measurements of altitude between the satellite and the surface of the ocean. Where a seamount rises from the floor of the ocean, its mass exerts a stronger gravitational pull, and surface of the ocean can drop as much as four inches, depending on the size of the mass. While seamounts were once thought to be merely navigation hazards, more recent exploration shows that they are “biological hotspots” for marine life. Their cone shape combines with ocean currents to push nutrients up towards the light, feeding coral, crustaceans, and fish.

If we think about how coral reefs form, one explanation for the Puerto Ángel fishing spot is that coral started to colonize the volcano while it was still above or near the surface. The coral wants to stay within sight of sunlight, so as the ocean collapsed or eroded the volcano back down below the surface (turning it into a seamount), the coral kept growing upward towards the light. There are three basic structures for coral reefs: build out from shore (fringing coral), create barrier reefs by starting from a fringing reef and joining individual reefs together, or by forming atolls, or circular reefs around a central lagoon. Charles Darwin proposed that atolls were formed when a submarine volcano subsided, leaving the circular reef to build on itself. In the case of Puerto Ángel, the reef went down with the seamount but kept growing upward toward the light, creating a terrific marine life habitat.

By Deborah Van Hoewyk